If you ask most people how they think Apple makes its money, they will probably tell you that they do it by selling iPhones. Although this is partially true, it is becoming less and less the case over time. As of the most recent earnings report from May 1st, about 45% of Apple’s gross margin comes from ‘services.’ This category includes things like App Store purchases, payments, and subscriptions.

Although the exact breakdown of the finances in this category is not public, a whole lot of it comes from what some folks refer to as the ‘Apple Tax.’ Apple very tightly controls what apps are allowed in the iOS environment, with a stated policy that iOS is a ‘walled garden.’ All apps in this environment are subject to the Apple Tax. This is the colloquial term for the 30% cut that Apple takes from all purchases of ‘digital goods’ in the iOS environment. This includes subscriptions or purchases made in the ecosystem. To put it simply and bluntly, a huge chunk of Apple’s money comes from them taking a cut of the microtransactions from your Auntie playing Candy Crush or your little cousin playing Clash of Clans. Not exactly the pioneering vision of tech innovation that Steve Jobs was talking about.

Growth on the product side of Apple has been pretty stagnant, if not a bit negative, in the past few years. Apple is big enough at this point that that is not a shocking indication that they are a failing company. They do a good job making products that people like, which is how they got so big in the first place. However, it isn’t enough to consistently make good products that people like at a reasonable margin; the profits need to keep growing, especially for these big tech companies that have driven the stock market in recent years.

The growth on the product side of Apple is also threatened by the tariff situation. Apple is big enough that it can shift US-bound production to places like India and Vietnam and away from China, where the biggest tax is being levied, but the company is likely to take a bit of a hit one way or another from this. This means that Apple will likely need to continue to lean on the services side of the business to maintain the unlimited growth that everyone expects from them. The problem is, they may have pushed it too far and lost that option.

Epic Games v. Apple - part 1

In August 2020, Epic Games (of Fortnite fame) launched a crusade against Apple that they referred to as "Project Liberty" in response to the walled-garden, Apple Tax situation. Epic wanted to bypass the App Store and start their own, or at least be able to do direct transactions with customers. Epic purposely broke its contract with Apple and launched an alternate payment system in the Fortnite app. This led to them getting banned from the App Store. Immediately after, Epic dropped a video on YouTube that is functionally an ad for the antitrust lawsuit they subsequently filed.

The legal theory that has driven antitrust enforcement since the 1980s is called the consumer welfare standard, which was created by Robert Bork. This theory argues that corporate mergers are better for consumers and, therefore, antitrust enforcement should not focus on ensuring competition. He also wrote a book called Slouching Towards Gomorrah about how The West™ has fallen because of egalitarianism. Cool guy, great stuff.

In Epic Games v. Apple, Epic argued that Apple had a monopoly over the App Store and iOS environment. This initially feels wild; Epic is saying that Apple has an illegal monopoly over its own product. But the App Store and iOS environment are also one of the biggest markets in the world for gaming, especially mobile gaming.

The lawsuit was first heard in the United States District Court for the Northern District of California by a Judge named Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers. Based on the legal standard and precedent at the time, she decided the relevant market in this case was mobile gaming transactions. Under this market definition, Apple is not a monopoly; competitors like Google and, to a lesser extent, Nintendo serve as valid competition.

Rogers ruled in Apple's favor in 9 out of 10 counts. On top of the loss in the antitrust argument, Epic clearly broke its contract. They were ordered to pay $3.6 million to Apple, and their ban from the App Store was upheld.

However, Apple did not get away completely scot-free. Rogers ruled that Apple had broken the California Unfair Competition Law (UCL) due to their ‘anti-steering policies.’ These rules prevent developers from telling users about other (often cheaper) purchase options outside of the walled garden. Apple restricted how developers could promote other options by restricting information within apps, banning contacting users directly (like through email), and disallowing developers from linking out of the ecosystem into the wider internet.

From the initial injunction on Apple:

Apple… are hereby permanently restrained and enjoined from prohibiting developers from (i) including in their apps and their metadata buttons, external links, or other calls to action that direct customers to purchasing mechanisms, in addition to In-App Purchasing and (ii) communicating with customers through points of contact obtained voluntarily from customers through account registration within the app.

Rogers made it clear that she thought it was reasonable for Apple to have some restrictions or charge some fees in exchange for the work they have done to build the ecosystem, but those restrictions and fees needed to be based on something. Apple was being anticompetitive, and as long as they stopped doing so, everything was going to be cool and chill.

This measured remedy will increase competition, increase transparency, increase consumer choice and information while preserving Apple's iOS ecosystem which has procompetitive justifications.

Epic Games v. Google

On the same day that Epic filed its lawsuit against Apple, it also filed a suit against Google and the 30% cut that Google took through the Play Store. The Google case took place after the Apple case, leading many to believe that Google was set for a slam dunk. There were, however, some key differences in the case.

First, Google doesn’t sell the phones that run Android, so the company has to control its ecosystem with third-party business deals. This means that their policies are much more public than Apple’s, which are notoriously locked down. The lawyers in this case could refer to the business deals that Google had made with Spotify or Netflix that come off as blatantly unfair, allowing the big guys to get away with sweetheart deals while little developers get gouged. Since intentions matter in antitrust cases, this kind of evidence can be incredibly helpful.

Also, during the case, it came out that Google had been purposely deleting evidence, which is certainly not a good look. Even within the evidence that made it to court, communications demonstrated anticompetitive behavior, which only made the missing evidence seem more sinister.

Perhaps the biggest difference, however, is that this case was being held in front of a jury instead of in front of a judge. The yucky business deals, shady emails, and deleted evidence made Google come off very poorly. During the case, the judge personally vowed to investigate Google because of how wild their conduct was. He claimed Google’s actions were “a frontal assault on the fair administration of justice,” and “I am going to get to the bottom of who is responsible on my own, outside of this trial.”

In this case, Google tried to argue that the market being discussed was digital transactions, which is a category so broad that it would be nearly impossible to have a monopoly. Epic made a similar argument as they did in the Apple case; the market was Android app distribution and Android in-app billing services.

The difference between the Apple ecosystem and the Google ecosystem is that Google’s is much more of an actual market. There is a Samsung Store that ‘competes’ with the Google Play Store, it’s just that no one uses it. The fact that there is more openness in the Google ecosystem actually made it easier to argue that they had monopolized it.

The jury was able to fill in what the market definition was on the verdict form, and fully sided with Epic. In 2024, based on everything that they had seen, the jury found that Google had an illegal monopoly in Android app distribution and Android in-app billing services. The case is being appealed, and who knows what may happen, but this decision was a massive shift from the Apple decision.

This very different outcome between the two cases also reflects a paradigmatic shift that has occurred in the last few years in antitrust law. Lina Khan and some other lovely folks in the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the US Department of Justice Antitrust Division have put in the work to shift the framing back to focusing on competition and more rigorous antitrust enforcement. On top of this, public perception of Big Tech has soured. More people are beginning to view these corporations negatively and want them to be regulated more. That shift between 2021 and 2024 does not explain the different outcomes between the Apple and Google case, but it certainly reflects it.

Europe

The European Union passed a new law that came into effect in 2022/2023 called the Digital Markets Act (DMA). This law was created specifically to go after large tech companies and prevent them from abusing their market power. The very first company the EU went after with this new law was Apple.

Under this new law, Apple now needs to allow third-party storefronts to be loaded onto iOS devices. This means the walled garden is out of Europe, and other app stores are now allowed. On top of this, just a few weeks ago, Apple was fined €500 million by the EU for its anti-steering policies. Along with this, Apple is now forced to open up its ecosystem and eliminate its anti-steering policies with much less forgiving language than in the original Epic Games decision:

Under the DMA, app developers distributing their apps via Apple's App Store should be able to inform customers, free of charge, of alternative offers outside the App Store, steer them to those offers and allow them to make purchases.

The Commission found that Apple fails to comply with this obligation. Due to a number of restrictions imposed by Apple, app developers cannot fully benefit from the advantages of alternative distribution channels outside the App Store. Similarly, consumers cannot fully benefit from alternative and cheaper offers as Apple prevents app developers from directly informing consumers of such offers. The company has failed to demonstrate that these restrictions are objectively necessary and proportionate.

As part of today's decision, the Commission has ordered Apple to remove the technical and commercial restrictions on steering and to refrain from perpetuating the non-compliant conduct in the future, which includes adopting conduct with an equivalent object or effect.

Epic Games v. Apple - part 2

But how did Apple get in trouble for anti-steering policies in Europe after it was told it had to get rid of policies by a US court injunction in 2021? Well, you see, Apple simply did not comply with the injunction. This is not my opinion, but the ruling of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California. To quote David Pierce from The Verge, “I think Apple basically got this ruling and had two years’ worth of meetings about how to give two middle fingers to this ruling.”

In 2024, Epic filed a request claiming that Apple willfully refused to comply with the injunction. During the subsequent hearings, “...the Court became increasingly concerned that Apple was not only withholding critical information about its business decision for complying with the Injunction, but also that it had likely presented a reverse-engineered, litigation-ready justification for actions which on their face looked to be anticompetitive.”

Apple was ordered to produce documents to support their claims, which they slow-rolled because “delay equaled profits.” This only served to make Judge Rogers angrier, which comes across in her writing. I highly recommend reading at least the first two pages of the ruling. Within it, Judge Rogers lays out Apple’s behavior, including a recommendation that Apple be investigated for criminal contempt.

27% apple tax

From the discovery documents, the court was able to see quite a bit about what options Apple weighed up. Fundamentally, two different proposals were set out on how to comply with the injunction: The first proposal was to eliminate the Apple Tax, but place some restrictions on the design and placement of links. The second proposal was to include a fee, but allow the links/buttons to exist with fewer restrictions. Instead, Apple chose the worst of all possible options: keep the Apple Tax and make the restrictions so draconian that no one would ever actually leave the ecosystem.

To make it legally plausible that they were following the injunction, Apple, and specifically Tim Cook, lowered the 30% Apple Tax to 27%. First of all, one of the main points of the original injunction was that the 30% fee was arbitrary and supracompetitive, and it is clear that this fee is the same. It is referred to as “again tied to nothing.” Phillip Schiller, a longtime Apple guy who worked with Jobs, pushed the team to eliminate the fee, but the finance team at Apple pushed to keep the fee as high as they thought they could get away with. Judge Rogers has this to say about the final decision.

Internally, Phillip Schiller had advocated that Apple comply with the Injunction, but Tim Cook ignored Schiller and instead allowed Chief Financial Officer Luca Maestri and his finance team to convince him otherwise. Cook chose poorly.

On top of this, any external payment service (like Stripe, for example) will charge more than 3% on any transaction. This means that it is not economically viable for any developer to switch at this 27% rate, functionally keeping them trapped.

Also, Apple added a rule where if someone clicks through to a website from an app, any transactions done on that website within the next seven days are subject to the Apple Tax, making the fees even more extensive than they had been even before the injunction.

restrictions on how developers can communicate with customers

Apple’s internal research suggests that two of the three best ways to “keep existing users coming back” are through push notifications and email outreach. To keep users paying through Apple, they maintained rules blocking developers from using either of these strategies.

Although Apple was required to allow developers to link out of the ecosystem, they imposed heavy regulations about how this was allowed. They interpreted the statement in the injunction: “buttons, external links, or other calls to action that direct customers to purchasing mechanisms other than in-app purchase,” as meaning that only one of those things had to be allowed, not all of them. This is a stupid, incredibly literal reading of the sentence and the kind of shit that makes people hate lawyers.

Apple allowed developers to add one singular link in their entire app, and it was required to be buried in the app, where it could never be found. Research indicated that pop-ups and placing the link in the in-app store would lead to the most conversions, so both of those options were banned.

design restrictions

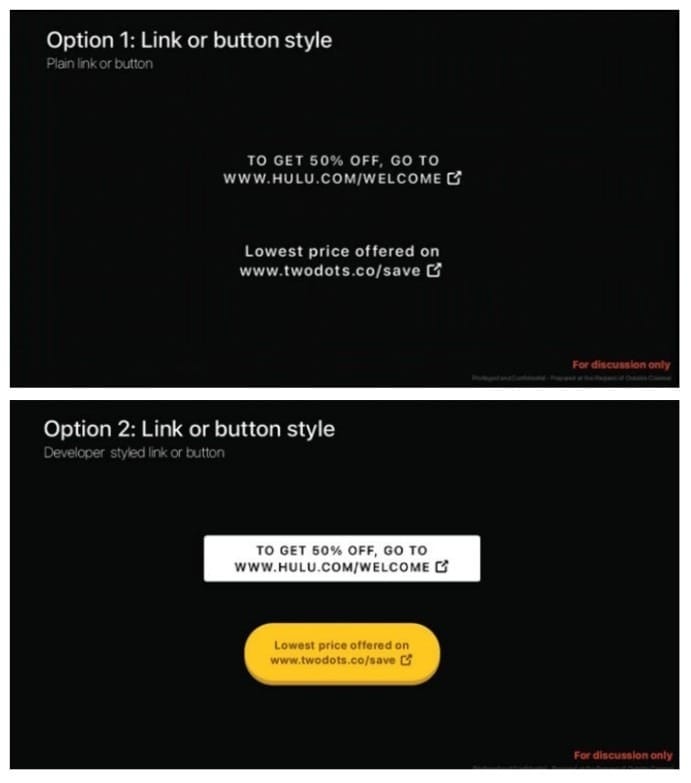

Apple also controlled both what the buttons had to look like and what they were allowed to say. Apple specifically chose designs that they knew from the rest of their business would lead to the fewest clicks, or what are called plain-link style buttons (top image), as opposed to any developer-styled button (bottom image).

The language that was allowed was also heavily restricted. The only phrases allowed to be used are shown in the templates above. Quite literally, these five sentences were the only ones allowed, even with all of the other restrictions.

adding even more friction

Also, these links had to be ‘static URLs,’ meaning that login information could not be passed through. This means if you hit subscribe on the link in the Spotify app, you would be taken to the website and need to log in again. Apple claimed that this was because of safety reasons, but discovery documents made it clear that they were merely adding another layer of friction to transactions outside the ecosystem. This is even more obvious when you notice that they use ‘dynamic URLs’ in the rest of iOS.

‘scare screens’

Finally, the most patently absurd claims made by Apple in this case were around the ‘scare screens.’ Again, Apple tried to claim they needed to add extra warnings for safety reasons, but when selling physical goods, which are not subject to the Apple Tax but would have the same safety concerns, these scare screens are not used.

The language in the discovery documents was wild. A UX designer literally said, “‘external website’ sounds scary, so execs will love it.” There are so many documented discussions about making the message ‘scarier.’ Apple defended this by saying that scary was an artistic word within the design community that meant something else:

“In terms of UX writing, the word ‘scary’ doesn’t . . . mean the same thing as instilling fear.” Rather, “scary” is a term of art that “means raising awareness and caution and grabbing the user’s attention.” [The UX employee] repeatedly asserted that the team’s goal was simply “to raise caution so the user would have all the facts so that they can make an informed decision on their own.” [The UX employee]’s testimony was not credible and falls flat given reason, common sense, and the totality of the admitted exhibits.

the new rules

Because “Apple knew exactly what it was doing and at every turn chose the most anticompetitive option,” they are now getting what, for them, is the worst outcome. They are no longer allowed to impose any fees. They are not allowed to restrict “content, style, language, formatting, flow, or placement” of any links or buttons that would direct people out of the ecosystem. They are not allowed to use scare screens. Developers are allowed to use dynamic links, reducing friction for transactions. And finally, Apple is not allowed to exclude certain types of apps or certain developers.

Judge Rogers closes with this:

Apple willfully chose not to comply with this Court’s Injunction. It did so with the express intent to create new anticompetitive barriers which would, by design and in effect, maintain a valued revenue stream; a revenue stream previously found to be anticompetitive. That it thought this Court would tolerate such insubordination was a gross miscalculation. As always, the coverup made it worse. For this Court, there is no second bite at the apple.

so what now?

Apple is going to appeal this decision, and we have no idea how that will go. But in the meantime, the floodgates are now open for a bunch of new possibilities. Developers will now be able to keep more of their revenue and/or lower prices for consumers. New products that couldn’t operate very well on over 30% margins, like ebooks or digital art, could start to expand. Payment companies can now compete on quality and price. Some cool stuff could come out of this, and in a world that currently feels pretty bleak, I am legitimately excited to see what comes next.

Apple is facing pressure from a whole bunch of directions. Unrelated to any of this, Apple may also be losing out on 20 billion dollars a year in pure profit. Previously, Google has been paying what amounted to 4-6% of Apple’s total profits to make Google the default search engine on Safari, but due to a recent loss in an antitrust case, Google may be forced to stop those payments.

Between the pressure on the product side due to the trade war, the elimination of the Apple Tax, and the loss of the free money from Google, Apple is going to need to start doing something new. Apple has been extracting ever-increasing profits without meaningfully expanding its offerings for years (unless you count the $3.5k VR headsets that made everyone nauseous). Macs, iPhones, and some of their other products have been genuinely innovative and useful, and I’m hoping that this situation pushes Apple back to trying to make new products that people want.

Big Tech has been stagnant when it comes to actual new products for about a decade now. These massive companies that account for a huge chunk of the economy are reliant on financial growth over innovation, and as the market gets more and more dependent on the growth of a few companies, this leads to significant precarity in the market. If Apple crashes and burns, it will cause some serious problems. Some people use this as an excuse to allow companies like Apple to continue on their trend of financialized growth, but that only kicks the can down the road.

Besides Apple, antitrust cases are going through the legal system for Google and Meta right now, cases for other Big Tech companies like Amazon are on the books, and the AI bubble seems like it could pop at any moment. But Apple, Google, and all these big players came out of the popping of the dot-com bubble and the Microsoft antitrust case in the early 2000s. It seems very likely that the tech industry is going to look very different in the next couple of years, but I feel pretty hopeful that those differences can turn out to be for the better.