A little while ago, I found myself at a Greek restaurant across from a man who studied English in school and works in a non-technical management role. We were discussing climate change. He explained to me how the markets would sort everything out. Climate scientists and activists were all being hysterical. We basically already have access to ‘unlimited free energy.’ This genre of person, the “climate change is real but the market and technology will fix it” folks, have some pretty fantastical ideas about the future: unlimited growth is possible and good.

The silly thing about this particular situation, eating my chicken gyro wrap as he did his monologue, is that I did my undergraduate capstone in chemical engineering on green industrial production. I did a full design, including costing and safety, of a blue hydrogen plant. I will admit that there are plenty of aspects of green energy that I don’t have high levels of technical expertise in, but I do think that experience and technical background makes me slightly more qualified to talk about green energy stuff. These types of folks tend to have almost no background in the stuff they are talking about and love making huge claims, so I figured my doing a deep dive would be fair.

The biggest current hype cycle in energy is nuclear. Now, I’m not a hardline anti-nuclear person, but the current hype cycle is not reasonable or realistic. Tech billionaires are just trying to avoid any public scrutiny of the way truly bonkers amounts of money and energy are being used on things like AI, so they are focusing on distractions. Don’t worry about AI’s power usage, we will just build nuclear plants to power them with zero emissions!

As a general rule, I think it is usually good to be skeptical of anyone who says that they have an obvious, easy solution to a big problem, and the only problem is that no one will listen to them. This is even more true if that solution serves the people in power. I have gone back and forth on nuclear power many times, and there are absolutely some reasonable points to be made for nuclear energy. Nuclear energy does not produce carbon or other greenhouse gas emissions. Big ups for that. If you had to build either a coal plant or a nuclear plant, I absolutely would vote for the nuclear plant. However, the only two choices are not coal or nuclear. Let’s run through some of the other arguments.

base load

The thing people like the most about nuclear energy, compared to things like wind or solar, is that it is ‘baseload’ energy. This means that it produces energy all the time, whereas wind and solar depend on external conditions. This argument makes sense until you realize one thing: nuclear doesn’t actually run all the time. These plants have planned closures for things like refueling and maintenance, and forced closures due to technical problems and safety issues.

Let’s look at France. France has the highest percentage of its energy produced by nuclear plants. Of Frances’ 56 operational nuclear plants, between 11 and 28 were not operating on any given day. Plants were closed an average of 127 days a year. Most of these are planned closures, but forced closures are not negligible by any means. France averaged 290 reactor-days of forced closures each year from 2019-2023, or about 5 full days per reactor per year. Nuclear fans love to talk about Dunkelflaute, or periods when there is no wind or sun. In Northern Europe, there are about 2–10 dunkelflaute events per year, with each event usually lasting a few hours to a day. The total combined duration of dunkelflaute time per year is usually about 50 to 150 hours, or about 2-6 days total. That means the unplanned non-operational time for wind + solar is about 2-6 days per year, and for nuclear is about 5 days per year. Seems like a comparable problem to me.

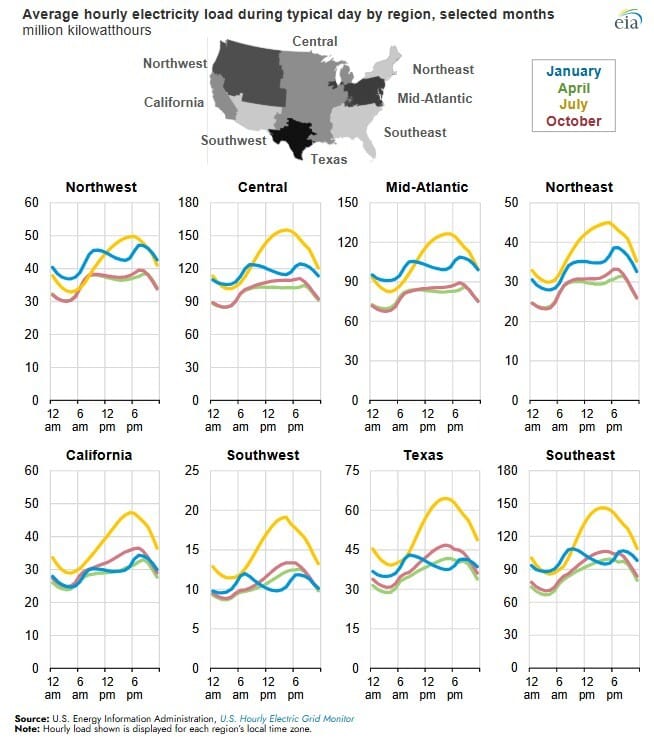

But not every single nuclear plant is out at once like a dunkelflaute. This is true. Using purely solar and wind does certainly leave gaps that need to be filled, but nuclear is not the only option to fill those gaps. Currently, in the US, most energy is produced using fossil fuels, and these plants create a mostly constant supply of electricity. However, demand is not constant. When demand peaks, we use “peaking plants,” where plants do something called ‘load following,’ or shifting energy production to meet demand. However, as we get better and cheaper energy storage, these plants are already being used less and less often.

On the flip side, when energy demand is low, the price of energy can flip negative. Negative price bids happen when plants would rather pay other plants to stop generating electricity than close down themselves. This is because shutting down and restarting industrial plants increases wear on components, which comes at a cost. This is an even bigger problem at a nuclear plant because the high capital costs of the plant mean that the wear is more costly. Nuclear is also bad at load following because of other financial incentives; nuclear plants have high capital costs and low fuel costs, so there is a high incentive to run them at full capacity as much as possible.

duck curves

For the most part, we can predict electricity demand fairly consistently based on time of day, seasonality, and geography. If we only use solar power, then there is an issue referred to as the duck-shaped curve. This is where electricity is overproduced during the day and then underproduced at night. Some folks think we solve this by increasing baseload power, but that would only increase the overproduction during the day. To me, this seems like a problem that should be solved using energy storage. The cost of energy storage declined 97% between 1991-2018, and continues to fall. Even conservative projections think that the price will continue to fall due to R&D and economies of scale.

seasonality

Either way, using solar panels alone is not going to work. Solar panels produce less energy during the winter, and it is not feasible to store energy on the magnitude of months’ worth of energy. The upside of the seasonality of green energy is that wind energy production tends to be complementary to solar. Solar is highest during summer and lowest in winter, and wind is lowest in summer and higher for the rest of the year.

geography

Geography has a huge impact on how electricity is and will be generated. Take the oldest form of how energy is generated, hydropower. Hydroelectric capacity is almost purely a geographical question. Countries like Canada, Sweden, and Brazil do way more hydroelectric energy generation than places like the UK or Germany just because of their terrain. There is a hard physical ceiling to that capacity. This highlights how the exact mix of energy production is not going to be the same from location to location.

Some countries will rely on some methods more than others, but another way to solve some of these issues is to expand the electrical grid. Europe is mostly interconnected, so energy can be shifted as supply and demand shift. This is helpful because too much supply can drive prices negative, and too much demand leads to outages, and spreading both over larger markets reduces the likelihood of either of these problems occurring. The US, however, has three different disconnected electrical grids. Updating and interconnecting our grid would allow us to address over- and underproduction by moving energy around based on supply and demand shifts.

Plus, other green energy technologies in development have some promise. Things like hydrogen, geothermal, and other fun new options may end up contributing more once they are ready. When it comes to green energy, I am a fan of throwing shit at the wall and seeing what sticks. Just because nuclear power seems like it isn’t going to be feasible to me doesn’t mean I want to ban it or whatever, and if it can be made effectively, it should join the party.

increasing energy demand and greenwashing

Until the last year or two, the US had had pretty steady energy demand for nearly three decades, and energy use has been going down in places like Europe and Japan. Electrification, or moving away from the direct use of fossil fuels, may contribute to some increase in electricity demands in particular, but the sharp increase in energy demand in the last year or two has come from the tech industry almost unilaterally.

Companies like Microsoft and Google have both pledged to be net-zero by 2030. How’s the progress on that? Microsoft’s emissions are up 30% and Google’s emissions are up 50% from 2020/2019, respectively. If this trend continues, we are all pretty screwed. To avoid criticism, these folks need to greenwash their companies so that they can avoid public outcry. Serious public backlash can hurt the bottom line, and we simply cannot have that happen.

They are using nuclear energy as an excuse. It isn’t realistic. Nuclear energy production is a long-term project. The timeline on these projects can be decades long. By the time any nuclear plants get built, if any even do, it will already be much past any of the deadlines these companies set for themselves. This is a distraction to avoid talking about broken promises and serious harm.

the most obvious criticism - time

The most recently completed nuclear reactor in the US is the Vogtle reactor in Georgia. This reactor is an AP1000 designed by Westinghouse Electric Company. The design is based on years of previous work, and still took about five years to design and get approved. The planning phase took about seven years, and construction took about eleven. That means from the beginning of design to completion, it took about 24 years to complete the project.

Between 2014–2023, the average construction time for a nuclear plant globally was 9.9 years. Construction times have gotten longer as time goes on. If that trend continues, it means that construction of a nuclear plant started today could reasonably be expected to take more than ten years to build. No matter how much power or money or whatever you throw at this issue, nothing is gonna make a bunch of nuclear power plants pop up fast enough to hit these promised targets.

what I think kills nuclear’s chances - cost

Because energy generation is so different between technologies, most analysts use something called the levelized cost of energy (LCOE). This takes all the capital, financing, and fuel costs and divides them by capacity to give us some numbers that make it easier to compare different options. The LCOE for nuclear power is higher than almost anything else under both best and worst-case predictions.

Also, nuclear has gotten more expensive over time, not less. Fracking has made fossil fuel generation super cheap, and things like wind and solar have wildly dropped off in price over time. These trendlines are the number one thing that makes me think nuclear doesn’t have much hope. On top of that, nuclear is also more sensitive to capital costs, meaning that instability is more likely to impact pricing. Based on *the times we are living in*, sensitivity to uncertainty is a real weakness that cannot be overlooked.

hype grifters

“At particular times, a great many stupid people have a great deal of stupid money” - Walter Bagehot, 1857

Transatomic Power was a startup out of MIT with a bunch of really fancy folks backing it in the 2010s. They said they were going to build a molten salt reactor (MSR) that was going to be able to run on spent nuclear fuel. It was going to be easy to build and cost-effective. It won a bunch of prizes and got a bunch of funding. That was until Kord Smith, a nuclear engineering prof also at MIT, pointed out there were some obvious basic physics mistakes and that “their claims were completely untrue.”

All the tech guys, like Bill Gates and Sam Altman, are all in on ‘advanced’ nuclear technology. Bill Gates has spent at least a billion of his own dollars on a nuclear company called TerraPower. Sam Altman is on the board of Oklo and has invested a chunk of change in Helion Energy, which does fusion instead of fission, making it even further away from current technologies. Very fancy people with lots of money.

Maybe these folks actually believe in this stuff, but they certainly trying to make money regardless of whether they are true believers or not. Oklo went public via a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) merger in 2024. This strategy allows a company to go public with less rigorous financial and operational disclosures. This strategy allows companies to make big claims with less liability, which seems particularly necessary in their case. They are claiming that they will have operating reactors by 2027, even though “it will probably take at least 4 years to obtain a license,” much less build the reactors.

Oklo also submitted a design with incomplete safety analyses to the NRC in 2022. They argue that their reactor is so safe that traditional NRC requirements are unnecessary, but they haven’t done the safety analysis. Personally, ‘trust me, bro’ is not my favorite approach to building expensive stuff that can explode; measure twice, cut once, my parents always used to say. Read a super vicious assessment here.

NuScale is another nuclear energy company. Founded in 2007, they originally projected that they would begin energy generation by 2015. They still have not done so in 2025. The 2018 cost projection for their 720 megawatt design was 4.2 billion dollars. By 2023, the cost projection was up to 9.3 billion, and the capacity projection was cut to 460 megawatts, or about 250% more per kilowatt than the big Vogtle plant in Georgia. Insiders started selling off stocks in 2023, and by 2024, NuScale laid off 30% of its staff. Maybe they can turn it around, but things certainly don’t look good.

but innovation can make nuclear cheaper and faster... right?

If the only goal was to get more nuclear power online quickly, there are a variety of strategies that could reasonably be taken. The fastest way would be to restart existing reactors, which some folks are trying. Completing projects that are currently idle would also be a reasonable strategy. Trying to come up with a brand new design is probably not. Designing a new nuclear reactor can take tens of millions of engineering hours. The French EPR2 design allegedly took about 20 million engineering hours to complete. On top of that, the cost of developing and certifying a new design is “on the order of roughly $1 billion.”

Currently, these new ‘advanced’ nuclear companies are not required to share much detail about their new reactors. A lot of them make some pretty optimistic claims. I’m going to go through some of these new designs and examine some potential issues, but one thing seems fairly important to note: these are nuclear engineering solutions to economic issues.

For serious proponents of nuclear energy, there is good reason to try to pursue innovation even if it means pushing the time horizon back. Folks at MIT have created a costing tool that will give investors a more realistic way of predicting costs, since the nuclear industry is so notorious for cost overruns. The tool takes some inputs, like estimated material volumes and labor force, and creates a more realistic cost estimate for projects. This kind of work, which focuses on where the costs and limiting factors come from, seems more promising to me, and I hope that it bears fruit.

small modular reactors (SMRs)

This is the big buzz phrase right now. The term SMR doesn’t even really have a distinct meaning anymore in the same way as something like AI, since it gets tossed around so much. The general concept is that you try to build a smaller nuclear reactor (usually around 30% capacity of a traditional reactor) using modular construction to lower initial costs. Modular construction is when more of the plant is built in a factory than at the work site. This lowers costs because factories are a more productive environment than construction sites. Modularization makes sense and is a good idea, but it isn’t new. The AP1000 included modular construction. Other industrial plants use modular construction.

The problem with making smaller nuclear reactors is that civil works, site preparation, installation, and indirect expenses are around 75% of the cost of building a nuclear plant. That means that the vast majority of costs are not reduced by all that much based on size. This will lead to capacity being reduced by a greater factor than costs, leaving the levelized cost of energy even higher than traditional large nuclear plants. Losing out on the economies of scale means that these reactors are even less cost-competitive than large nuclear reactors.

Also, the idea that SMRs are going to be faster to build seems similarly unlikely. The only SMRs that have been built are in Russia and China. The Russian SMR took 13 years to build, and the one in China had the longest construction time of any Chinese-designed nuclear plant. This is because supply chain issues lead to significant delays. There is a chance this can be improved moving forward, but that would require bucking the negative learning trend that nuclear has been in for a while. We can throw a bunch of money at this and see if it works out, but other technologies are further along and have fewer risks, so I think it makes more sense to focus on those.

High-temperature gas reactors have previously operated in the US, UK, Germany, Japan, and China. These reactors had issues, like component degradation and higher fuel costs, so most of them have been shut down. There are only two commercial sized high-temperature gas reactors currently operating, and they are at one plant in China. The projected build time was 50 months, and it took 10 years to build. Also, these reactors operate at about 10% of capacity because of technical issues. Bad outlook on these.

These guys are Bill Gates' favorite. Fast neutron reactors can get better fuel utilization, which is great. However, they are more expensive and complicated to build, exacerbating nuclear power’s weaknesses. Also, sodium reacts violently with water, burns in air, and can interact with stainless steel in a way that causes leaks. This leads to serious material integrity issues that lead to accidents at the EBR-1 reactor in Idaho and the Fermi-1 reactor near Detroit. The cores heated up and blew themselves apart. These designs are less safe, more expensive to build, and more likely to be delayed. Also not super promising.

Saving my favorite for last, the molten salt reactor. The biggest upside of molten salt reactors is that they can change output much more quickly than any other design. This means that they could be great peaking plants. Also, these reactors tend to operate at lower pressures, meaning that explosions are less likely.

On the flip side, they also include having reactor components in chemically corrosive, hot, radioactive environments, which is not a state any materials want to be in. This leads to integrity issues and means that these reactors will either not last as long or need more frequent and extreme maintenance. If any materials folks can create a new super metal that can deal with this environment, these would be super cool. I just don’t know if the laws of physics are going to let us get away with it.

Microreactors are super tiny nuclear reactors, usually defined as having a maximum capacity in the ballpark of 20-50 megawatts. The main issue with these guys is that even if you can manufacture the reactor itself for free, the fuel costs will be prohibitively high in almost all use cases. The explanation of this is super technical; listen to a real nuclear engineer explain here.

The only real application possibility seems to be to replace diesel generators in remote contexts like arctic communities/outposts, mining, or military stuff, but even then, it will probably be more expensive than what we currently use. The idea that a bunch of microreactors are going to be used to power data centers or cities does not make sense based on basic physics principles, at least based on my current understanding.

regulations

Nuclear energy is a bit like the airline industry. The number of people killed by nuclear plants is much smaller than something comparable, like chemical plants. The number of people killed in airplane crashes is much lower than car accidents. But if an airplane crashes, people freak out, and the industry takes a beating. This is similar to the nuclear industry. After the Fukushima meltdown, a bunch of nuclear plants were shut down, and nuclear bans got a lot more popular. If another meltdown occurs, more shutdowns and bans are going to happen. You can scream about that being irrational all you want, but it is reality. It just means that the safety standard needs to be higher.

Nuclear regulations are not perfect. If folks want to quibble with any in particular, that is totally fine. However, the idea that regulations are the limiting factor is simply incorrect. There are a whole bunch of plants that have been approved for years but have stalled because they were not economically viable. The plants that have stopped operating have mostly cited operating costs to explain why they are shutting down. The main problem is the money, not the rules.

But the rules are the thing making it so expensive, you may say. For one thing, the current regulatory scheme in the US is arguably better than it was during the heyday of US nuclear power. Under the old rules, you had to get a construction permit and an operating permit separately. That means that you could get a construction permit, build an entire nuclear plant, and then not get an operating license, wasting billions. Now, all of the approvals happen at once, streamlining the process. Also, standardized designs only need to be approved once, so you can skip this process completely if using an existing design.

But these approved designs are more expensive, you may say. The first reactor design approved under the current rules was built in Japan in less than four years and cost about 40% less than the other reactors built in Japan at that time. Most of the costs of a nuclear plant come from material and labor costs, and most of the Gen-III designs are simpler and use less material than older designs. The cost increases are coming from somewhere else. Better regulations are not going to solve the underlying problems here.

accidents and ‘de-risking’

Nuclear meltdowns are possible, and no amount of safety features will ever make the chances zero. Theoretical models can say the risk is whatever tiny number, but reality isn’t as perfect as models. Accidents tend to be emergent, so existing safety features won’t prevent them. The Fukushima meltdown was caused by “a situation we had never imagined.” When systems are super complicated, more things can go wrong.

Talking about the public health and safety impacts of these accidents is not super productive. Pro-nuclear folks tend to minimize real concerns, and anti-nuclear folks tend to get a bit hysterical. Instead, I think it makes more sense to talk about the financial cost of these accidents. After the Fukushima meltdown, between the payouts to the affected people and the cost of cleanup, the estimated cost of the meltdown is in the ballpark of $200 billion. The Japanese government gave TEPCO (the company that operated the reactor) about $70 billion in zero-interest loans. Of that loan, about $68 billion has been delayed. TEPCO is a publicly traded company that makes profits, but when something like Fukushima happens, the public is expected to pick up the tab. When we live under a system of privatized profits and public costs, choosing an option like nuclear is a little wild.

Earlier this year, the head of the International Energy Agency (IEA) told reporters that “Private investors, major banks and tech companies are showing interest in the European nuclear industry, but governments need to lower risks to encourage investment by guaranteeing contracts.” The government is expected to ‘de-risk’ nuclear for investors, meaning that they say they will pay if things go wrong. Even if you remove meltdowns entirely, the risk of these projects getting derailed before breaking even is huge. Investors want the government to pay for the problems, but let them get the profits. Especially when nuclear is also already more expensive than other forms of energy, these profits come from higher prices for regular people who are also going to be on the hook if something goes wrong. Not a great deal.

Waste/Decommissioning

After a nuclear plant shuts down, it takes decades to decommission. Some plants are ‘mothballed,’ or shut down in a way that allows for possible future restart. There are, however, costs associated with this. That means that if we don’t have plans to get them back online, they are just going to continue to rake up costs without producing anything.

The estimated cost of decommissioning the current nuclear fleet is $150 billion. Already, the government spends billions of dollars a year on the storage of nuclear waste. The cost of nuclear waste to the US taxpayer reached $30 billion per year in 2018, of which $18 billion was from nuclear power and $12 billion was from nuclear weapons. These costs aren’t going away any time soon, since the half-life of some of these materials gets up to the 15 million-year range. How much more of this waste do we really want to pay for?

future hopes/predictions

In general, the current hype around nuclear energy seems mostly detached from reality. ‘Advanced’ nuclear technologies seem likely to be more expensive and harder to build than existing technology, and even in a best-case scenario, are at least a decade away from being built. Despite the rosy projections and hype, making even less cost-effective nuclear plants just because the overall cost is smaller seems like a bad long-term strategy.

On the flip side, banning the operation of nuclear plants, as was done in Germany, seems counterproductive, at least for the time being. Before we reach a tipping point, nuclear plants are much preferred to coal or other carbon-intensive alternatives. In the near term, nuclear plants will likely continue to operate, especially if they are subsidized or state-run. Some places with command economies, like China, might continue to build nuclear power plants since they are insulated from market forces, and militarized countries like the US will refuse to totally eliminate nuclear power because of the weapons angle.

Markets are not going to naturally gravitate towards something that requires huge up-front costs, long break-even times, and will probably never be as cost-effective as a range of alternatives. Hey, maybe this is how we find out that the US really is a command economy, but with the command coming from tech billionaires instead of the state. We shall see if the overlords’ whims remain and if so, prevail, despite the inverse market incentive.

For genuine proponents of nuclear energy, do you really think that the ‘move fast and break things’ crowd are the folks you want to rely on for the nuclear industry to make a comeback? Is this group of people able to provide the level of support necessary over the timeframe required to see things through to reality? I think it’s more likely that these folks throw a bit of money at this stuff, then get distracted and move on. Not good for the industry long-term.

I think prioritizing green energy that is faster, cheaper, and easier to build, and more cost-effective in the long term, is a better strategy for combating climate change, but if folks can figure out a way to make nuclear power cost-efficient, amazing. I think it is more likely that nuclear fades away as it loses in the market. But hey, there are some really smart folks working on this issue. I truly wish them the best and hope they can find a way to make nuclear power feasible, because a bunch of nuclear plants is way better than a planet on fire.

Thanks for reading! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Further Reading/Watching

Lazard LCOE Report 2024 - costing report on different energy sources

Nuclear is Not the Solution by MV Ramana

Decouple Podcast - explicitly pro-nuclear podcast